Thank you to those who came. A lovely time with wonderful people doing writerly things among an inspiring place. Thank you to Poor Richard’s for their continued support in this ongoing literary project.

Thank you to those who came. A lovely time with wonderful people doing writerly things among an inspiring place. Thank you to Poor Richard’s for their continued support in this ongoing literary project.

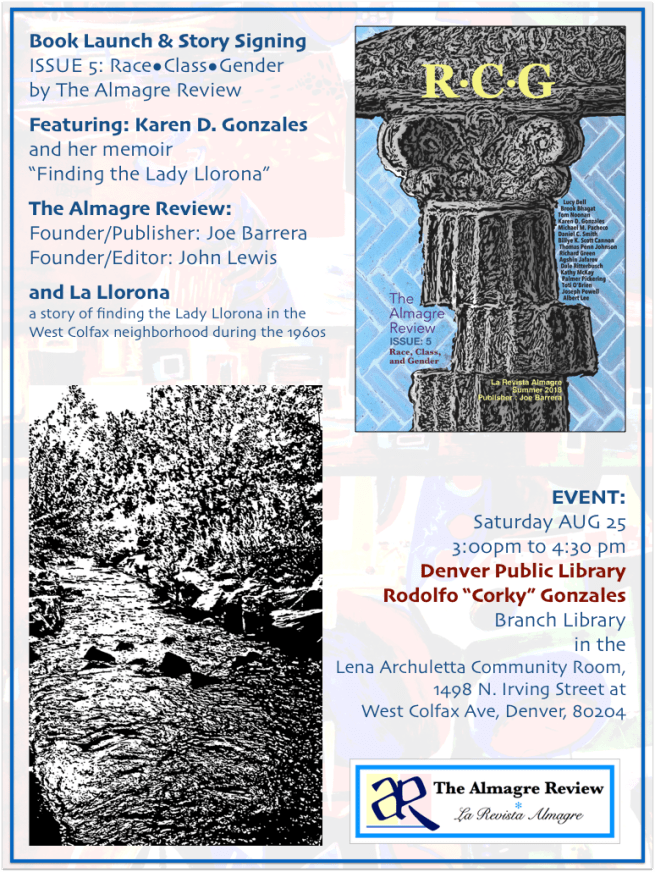

Come join the growing Almagre community this Saturday up in Denver. Issue 5 contributor, Karen D. Gonzales, will be reading her memoir about encountering the legend of Lady Llorona.

go to: DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY

~Hope to see you there,

the Almagre Staff

It’s here! After a lot of work, Issue 5 has arrived. We think you’ll find it a worthy read, with challenging and provocative pieces, but also with a thread of hope and growth throughout. A special thanks to our sixteen contributors who made this issue possible. Please take the time to purchase a copy. Support art, support creativity, support our efforts to rebuff the world fed to us in captions and tweets. BUY RCG.

The Almagre Review can also be purchased at…

Show up at one of these locations, ask the proprietor for a copy. The brick and mortar literature store is a bulwark of civilization!

Come join The Almagre Review at Rico’s Cafe (1247, 322 N Tejon St.) this Sunday from 2 – 4 PM. This is an informal celebration of the publication of our fifth Issue, made possible by so many contributions from our local writing and reading community. Contributors to Issue 5 are welcome to read their piece which appears in “Race, Class, and Gender.”

All are welcome. This is a casual affair, enjoined to the mild intoxicant of caffeine and married to the general joy of the written word. Along with contributors, we hope to hear from local readers and writing enthusiasts, so come with your favorite literary topics at the tip of the tongue.

~The Staff

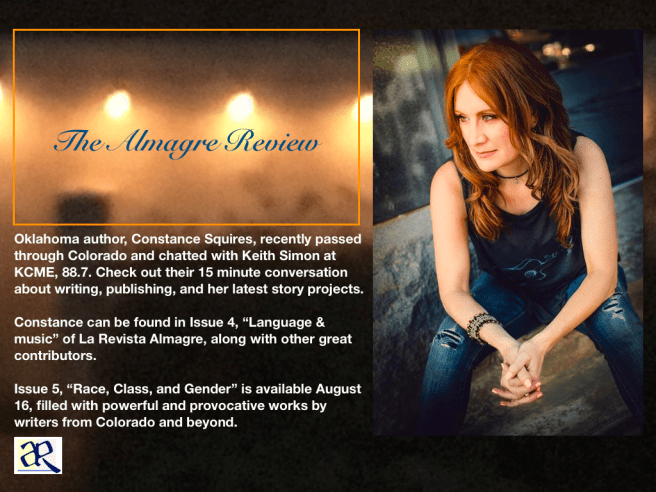

Here at our journal, we’d like to take a minute and say thank you to local hero, Keith Simon, whose tireless work and support for fellow Creatives is truly a gift to Colorado Springs and the Front Range. Keith is the host of the Culture Zone, a weekly radio show where he chats with local makers of art, music, literature, and more.

It’s finally on its way, official release date included: August 16.

The staff of The Almagre Review would like to thank our community for their patience. We missed our usual July deadline, and some of that has to do with bringing together an issue with challenging themes. We hope all may find elements that teach, instruct, and illuminate. And with humility, we acknowledge that this area of literary exploration could never be captured in 140 pages. This is our small contribution into the much larger pool of experience, and we hope you find time to be a part. Without a doubt, this issue is made possible by the wonderful authors and poets who honored us with their works. Our journal is indebted to them.

We will continue to provide updates as we move closer to the release date. Please feel free to tug our sleeve, Joe Barrera at jjbarr46@gmail.com, or John Lewis at larevistaalmagre@outlook.com.

Thank you all who have helped bring this edition to fruition,

The Almagre Staff

I often wonder why U.S. schools ignore so much that is important when teaching history. It’s a strange thing for a patriotic people, but much of mainstream history is unknown, leaving students ignorant of the foundations of the country. “Minority” history, of course, is almost a complete blank. The Southwest, in particular, is ignored. I tell anybody who will listen that history is important, but as a young man once said to me, “I don’t need to know that because it happened before I was born.” In my eternal quest for enlightenment, I was in Taos last week at the annual international meeting of the Anza Society, a group devoted to research and education on the life and times of Juan Bautista de Anza, the Spanish governor of New Mexico, 1777-1787, and intrepid trailblazer who explored much of what is now the U.S. Southwest.

Anza’s main claim to fame is the campaign against the Comanche Indians, led by a chief named Cuerno Verde, who wore a buffalo headdress with green-painted horns, hence the name, Greenhorn. In 1779, Anza led a large force of Pueblo, Ute, and Apache Indians, along with presidial troops and New Mexican settlers, down Ute Pass through what is now Manitou Springs and Colorado Springs. This was a trail-blazing feat which is only poorly known. Known or not, the Spanish and Indian presence here makes me feel good. I am happy that our patch of ground was the site of events important in the history of the region. The war against the Comanches is important because it shows Anza’s genius, his ability to organize an allied expedition of Native Americans, Spanish soldiers and mestizo settlers against the destructive Comanches who were raiding in New Mexico, indiscriminately attacking indigenous people and settlers. Anza took the Comanches camped along Fountain Creek by surprise, ultimately defeating and killing Cuerno Verde near what is now Walsenburg. This victory and other battles resulted in the Anza-negotiated Comanche Peace of 1786, saving the remote colony of New Mexico from likely destruction by the fierce Comanches. This puts Anza in the same league with famous American frontiersmen, people like Daniel Boone, Kit Carson, John C. Fremont, and Lewis and Clark. Yet we never hear about him. Fortunately, a group of dedicated community leaders are planning a Colorado Springs Anza Memorial at the confluence of Monument and Fountain Creeks, possible site of the first skirmish with the Comanches as Anza descended Ute Pass.

Sometimes history can play tricks on you. I was with the Anza conference attendees when we toured Taos Pueblo. On the edge of the adobe apartments of the thousand-year-old Taos Pueblo are the ruins of the church of San Geronimo, destroyed by Colonel Sterling Price’s 2nd Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers and Captain John Burgwin’s 1st U.S. Dragoons in February, 1847. The New Mexican and Taos Indian insurgents had revolted against the American occupation, killed the governor imposed on them by the U.S. Army, and were now holed up in the church. I gazed at the wooden crosses in the campo santo, the church-yard cemetery, the mounds of decomposing adobe bricks, and the bell tower that still stands, repaired just enough by the Taos people to keep alive the memory of their slain compatriots. Then I saw the dragoon captain rally his troops for a charge. He was out in front. He fell, mortally wounded. At that moment I felt that I was fated to see what once was, was not now, invisible, but yet still visible. It was real to me. I suppose the experience just came from the knowledge of history.

Joe Barrera, Ph.D., is the former director of the Ethnic Studies Program at UCCS, and a combat veteran of the Vietnam War.

Once upon a time there was an emperor who wanted to make his country great again. He thought, “if we conquer more lands we will become even more feared and respected. If we send the army on an extended deployment we will find the military glory we have always wanted.” Thinking like this, the emperor knew that he had to find a country that would be ripe for the taking. Trouble was, all the neighboring empires were too strong to attack. The emperor didn’t like it, but he was compelled to look far away for a weak country to conquer. Try as he might he could not find one. Then he had a stroke of luck, or so he thought. It turned out that there were some wealthy people who had been driven out of their own country by a revolution and were now living in the capital city. They decided that they had the answer to the emperor’s problem.

The exiles went to see the emperor, who at first received them with some skepticism, but then became quickly interested in the scheme they proposed. “The man who is now president in our country,” they said, “is very unpopular and could be easily overthrown by the army of Your Imperial Highness. Not only is he unpopular, he is also a radical socialist who has confiscated our estates and left us destitute. He deludes the masses by pretending to liberate them from the tyranny of the rich.” The emperor heard this and felt a twinge of conscience. He knew that many of his own subjects were chafing under the oppressive social order he was enforcing. But not to worry. He felt very secure in his power. The oily exiles continued with their blandishments. “Your Highness could appoint your nephew, the Archduke Maximilian, to be the king of our country. He is a man who is ready to serve you and is just looking for an endeavor worthy of your greatness. The people will welcome him with open arms. They will throw flowers at your soldiers when they invade our country. The people will embrace your enlightened rule and all the benefits it will bring.”

The emperor believed them. He sent his army with the Archduke at its head across the sea. But the promises of the exiles were a pack of lies. The president was not unpopular. The people did not welcome the foreign soldiers with bouquets of flowers. They resisted the invaders and mounted an insurgency that lasted for years. The president led the guerrilla war and was never caught in spite of many defeats by the superior forces of the empire. Finally, the emperor gave up. He recalled his army and as soon as the soldiers left the Archduke was shot by the insurgents. The emperor who had dreamed of glory was himself soon deposed when another stronger empire invaded his country.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? With a few minor changes this could be the story of our involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. In this sense it is a cautionary tale for the United States. But this is the story of Mexico and France, and el Cinco de Mayo. Emperor Napoleon III, nephew of the first Napoleon, had delusions of grandeur. These were shattered at the Battle of Puebla, May 5, 1862, when a rag-tag Mexican army defeated the vaunted French. The battle started a war that lasted until the French were driven out Mexico. This flagrant European colonialism–the attempt to make brown-skinned people subject to white-skinned people–has become a lesson that teaches freedom. But we don’t know this. Instead, we have American el Cinco de Mayo, time for parties, time for Latinos and Anglos to get gloriously drunk and make the beer companies rich. If only we knew its original significance. The real meaning of this holiday is that we need to “decolonize” our minds. To “decolonize” means that we throw off the mental shackles of inferiority. For U.S. Chicanos, inferiority is always a problem. This is because we are always fighting inferiority, something that is more real internally than it is real externally. Mexican Americans can look at Black Lives Matter and at the Me Too Movement for inspiration. These are examples of human beings reclaiming their own inherent self-worth.

Joe Barrera, Ph.D., is the former director of the Ethnic Studies Program at UCCS and a combat veteran of the Vietnam War.

For Issue 5 of La Revista Almagre/The Almagre Review we are looking for fiction, flash fiction and art on the themes of Race, Class, and Gender. We would like contributors to submit short stories (and other forms of fiction) that explore the realities of these social categories in the U.S.

To be clear, we are looking for insightful fiction that is powerful and illuminates that which divides us in society, how people engage in conflict with others, and sometimes build bridges across the divides. We want a diverse group of contributors, especially works from people of color — African Americans, Latinos/Chicanos/Hispanics, Native Americans, and Asian Americans.

We also want fiction on issues of gender, how women see themselves, their relationships to men or their refusal to be defined by their relationships to men, and of course their changing roles in society. This does not preclude male perspectives. Too often men feel that their views on gender are not valued in the discussion. We want to change that, especially in regard to how masculinity is understood.

And then there’s the issue of class. For this category we welcome the perspectives of working class people, those who are sometimes called “the working poor,” even the homeless. We would like to see an often ignored category — the white working class perspective. At the same time we realize that social class is a reality that underlies and helps to define the other two categories. What this means is that anybody can write about “class,” regardless of where she or he fits in the social hierarchy.

We don’t want the kind of writing that is typically found on blogs, or the kind of expression we hear on politically oriented talk shows, or on TV news interviews. That sort of thing has its place. However, we are looking for something deeper, and, yes, more sensitive. What we want is for you to invite others into your world, to tell them about how you see things, your perspectives, your experiences. We want to create unity. The way we see it, right now the American quilt has too many people snipping at the hems and seams, disuniting our narrative. We are looking to build an issue that allows readers to walk in someone else’s shoes — easier said than done. In spite of the cliché, “to walk in someone else’s shoes” is a much-needed experience in this polarized society of ours. And in the end, your fiction must still hold up as a well-written story.

We look forward to reading your submissions. Everything that is submitted to us is carefully considered. There is no submission fee, but in the interest of artistic solidarity, please consider buying a copy. Every cent goes into the next literary theme.

Sincerely,

Kirsten Alires, Editor

Kayla Sibigtroth, Editor

John Lewis, Principal Artist

Joe Barrera, Publisher

The Almagre Review/La Revista Almagre

A literary journal founded and published on the banks of el Rio Almagre, an ancient name for Fountain Creek, at the foot of Pikes Peak on the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies.

On Feb. 3, 1968 I was sitting on the banks of a muddy river in the village of Thanh Canh, or as we called it, Tin Can. I never learned the name of the stream. Reflecting on that time, Tet 1968, I see a microcosm of our misadventure in Vietnam. The situation revealed lessons we should have learned but did not.

Convoys of U.S. and South Vietnamese jeeps, APCs (armored personnel carriers), trucks loaded with troops, M-48 tanks, dusters (armored vehicles with 40mm cannons) crossed the river on a pontoon bridge. The convoys looked powerful but it was an illusion. On one side of the bridge there was a French fort, an enclosure surrounded by berms, mounds of dirt. The defenders burrowed into the mounds to make fighting positions. We called it the “mud fort” because it was just a triangle of muddy dirt, a relic of the French Army’s futile attempt to control Annam. The fort was a harbinger for us. Along the river, bamboo hooches (shacks) stretched for several kilometers. The fort was manned by the Regional Forces/Popular Forces, RF/PFs, trained by U.S. Green Berets, part of our futile effort to control Vietnam. We called them “Ruff Puffs.” They hid in the fort at this crossing on the road between Kon Tum and Dak To and never came out. We were out all the time. We walked up to the French mission. There were dozens of kids, Vietnamese nuns, an exquisite Catholic church, an ascetic French priest–the lone survivor. The mission, the church, the mud fort. I doubt that anything is there anymore. Shades of Beau Geste and the Foreign Legion.

A horde of villagers came running downstream and into the ramshackle fort. The North Vietnamese were advancing. They were a short distance away. Immediately, the U.S. tanks patrolling the road formed a defensive lager next to the fort. We infantrymen had to content ourselves with holes along the banks. But all was quiet. That night one of the tankers fired H&I (harassment and interdiction) up and down the river with his M79 grenade launcher, which fires a 40mm projectile. In the morning the Ruff Puffs yelled and shook their fists at the tanks. The H&I had sunk numerous sampans, boats the villagers used to fish in the river. There went their livelihood. So much for winning hearts and minds.

In the afternoon loin-clothed Montagnards filed into our perimeter. Their leader, a dignified old man, sat down with us. I gave him a can of Coca-Cola. He drew a map in the dirt. We compared our map to his. The others were disdainful but I insisted that he was telling us something: a concentration of NVA troops. I read the coordinates and convinced one of the tankers to use his powerful tank radio to call in an air strike. The jets came in. That took care of the imminent threat. The Montagnards melted into the forest. Did they escape reprisals from the North Vietnamese?

We won every battle in Vietnam, including Tet, but lost the war. There are reasons why we lost in Vietnam and are bogged down in our present wars: We have good motives but our empire treads the path of older empires. We do not effectively engage the enemy. We are too road-bound, too inflexible. We build too many “mud forts.” We do not understand local cultures and alienate our friends. We dismiss nationalism, the impulse to throw out the foreign invader and recover past glories. Nationalism inspired by religion is what motivates our present enemies. It’s almost impossible to stamp out, and now it has terrible forms–the Taliban and the horribly twisted ISIS.

Joe Barrera, Ph.D., is the former director of the Ethnic Studies Program at UCCS, and a combat veteran of the Vietnam War.